Bletchley Park

The Bletchley Park Science and Innovation Centre.

The green building to the left of the image is Hut 8, which dealt with German naval Enigma messages under the lead of Alan Turing.

The cinema shows WW2 newsreels.

It was a rather rainy day so I didn't take many pictures outside!

An Enigma machine with the three scrambling rotors at the top and Steckerbrett (plugboard) on the bottom front edge.

Kindly ignore the anorak in the reflection of the glass case.

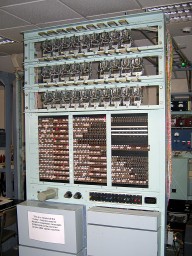

The front of the rebuilt bombe.

These were used to help decrypt messages generated by the Enigma machine. Each drum performs the equivalent function of one of the rotors in an Enigma machine, hence the grouping in threes (one for each of the rotors in a three-rotor Enigma). The bombe could perform the same task as thirty-six Enigmas running in parallel, and was driven by an electric motor to quickly step through all of the different rotor positions.

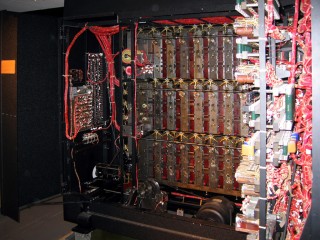

The inside of the opened bombe, showing some of the mechanical detail behind the drums to the left (with the electric motor at the bottom) and some of the electronic detail in the door to the right.

A bombe apparently contained approximately five miles of wiring.

Some more detail of the inside of the bombe. The bundle of wires to the left of the image are connected to a bank of control switches and the start/stop lever.

This plugboard replicated the function of the Steckerbrett on the Enigma machine, using 26-pin connectors.

A Lorenz cipher machine, which provided much stronger encryption than the Enigma machine and which therefore required a much more powerful machine to help decipher its messages.

One of the early machines used to help decipher the Lorenz cipher, named the "Heath Robinson" after the cartoonist.

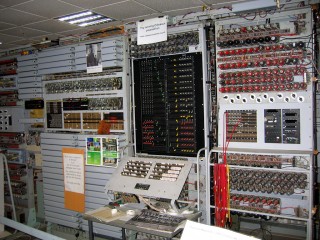

Colossus, generally regarded as the first digital electronic programmable computer, followed the Heath Robinson.

This is a Mark 2 version. After the war, the original computers were dismantled, the parts sold as military surplus and the plans destroyed - this machine was rebuilt from memory and a few black and white photographs, with the task finished in 2007.

This high-speed (5,000 characters per second) paper tape reader is used to input the encrypted message where it is compared to an internally-generated message generated by a simulation of the Lorenz machine.

When a likely match for the initial pin configuration was found it was printed on an electric typewriter.

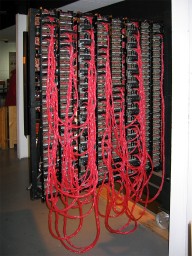

The Colossus Mark 2 was powered by a whopping 2,500 valves, some of which are pictured here. The heat coming off the machine was quite intense!

Valves have a habit of burning out, a concern with the original design that was resolved by never switching the machine off. As this is not possible with the new machine it is carefully warmed up in the morning and then cooled down at night over a period of hours.

The black valve at the left of the three rows of red valves apparently dates back to the war.

A view between the front and back of the Colossus, showing some more of the valves (the front of the machine is to the right of this picture).

Replacement valves are apparently sourced from ones left over after telephone exchange upgrades.

This "Tunny" machine was built to emulate a Lorenz machine. Once Colossus had found the initial pin settings for the message, this machine could be used to decrypt the message.

Bletchley Park also houses The National Museum of Computing. Here are a collection of machines that are completely self-contained (no external wires connecting the parts together). How many do you recognise?

A computer used for air traffic control. The left cabinet ("display processors") contains two PDP-11/34s, the one to its right ("radar processors") contains two PDP-11/84s.

The Harwell Dekatron Computer, aka "WITCH" (Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computing from Harwell), under restoration.

This is an early relay-based British computer. Dekatrons (one of which is sitting on the table to the left of the picture) were used for volatile memory.